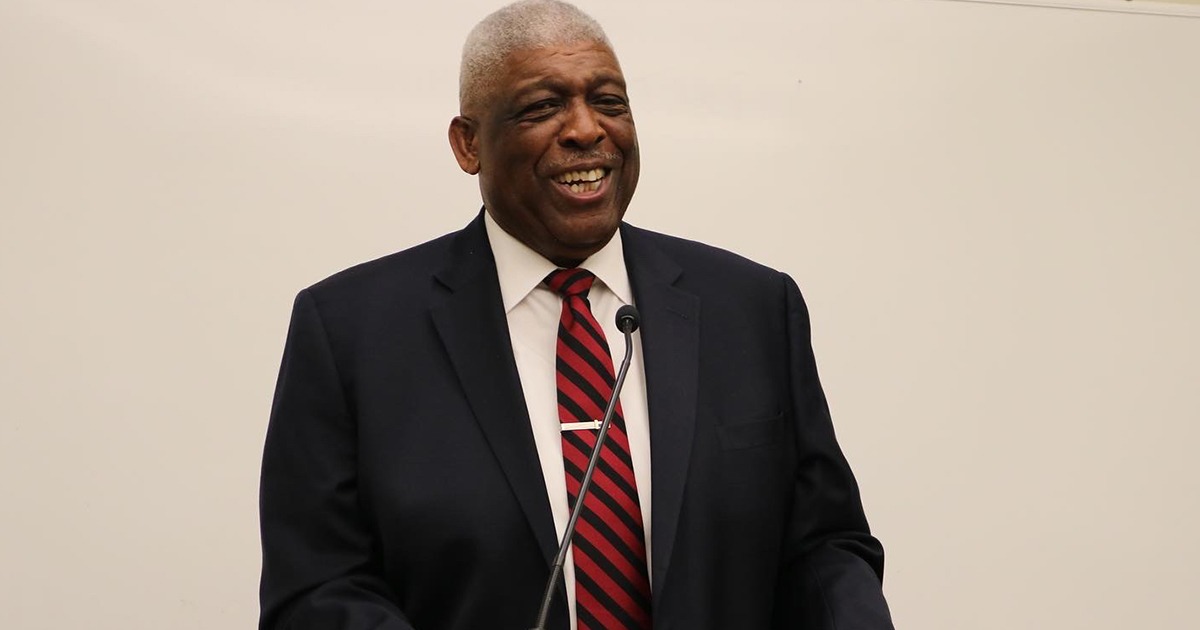

Former Sen. Floyd Nicholson delivers poignant, personal address on civil rights history in U.S.

Presbyterian College launched its celebration of Black History Month with a story told not only by someone with knowledge about the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s but also someone who experienced it.

Former S.C. Sen. Floyd Nicholson’s address during the college’s annual Dr. Booker T. Ingram Jr. Convocation and Lecture was a personal account of what it was like growing up black in the South during the tumultuous 1960s and some of the biggest events that shaped U.S. history.

Nicholson said his father died when he was only six years old and his mother, who had no formal education, was a domestic worker who moved the family often to live wherever she could afford rent. He grew up going to segregated schools the U.S. Supreme Court declared “separate but equal.”

“Part of that was right,” he said. “The separate part. The equal was not right. There was no equality. We would go to places where, on one side, it said ‘whites only’ and the other side said ‘colored.’ You looked on the white side, it was all immaculate. It was set up nice. You go to the other side, the colored section was run down. They didn’t keep it up or anything.”

In school, Nicholson said he discovered the textbooks he and his classmates read were used and passed down from white only schools.

But there were two years in the 1960s – 1963 and 1968 – that illustrated how turbulent that era was in the United States.

In 1963, Nicholson said, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. lead a march in Washington in support of black and poor people. There was hope, he said. But it was dashed by the news of the Ku Klux Klan bombing the 16th Street Baptist Church killing four black girls. Hope also took a blow when U.S. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. And then there was Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s “segregation then, segregation now, segregation forever” speech to prevent black students from attending the University of Alabama.

“But, you know what?” her said. “Everything changes. Before he died, (Wallace) retracted those words. He admitted he was wrong. But I remember at the time fearing for those students. Going to school with guards. Being spit on. Kicked. But they endured.”

Five years later, the country again was gripped racial tension, an unpopular foreign war, and violence, Nicholson said. The first event in 1968 was personal and involved Nicholson as a freshman on the campus of S.C. State University in Orangeburg.

A few S.C. State students tried to enter a “whites only” bowling alley across the street from campus and were turned away by its owner. The next night, a larger group of 200-300 students returned but were forced back onto campus by the police. The State Law Enforcement Division and the S.C. Highway Patrol surrounded S.C. State to make sure students were not able to leave campus. While students continued to protest at the front of the university, officers began firing – killing three young men and injuring dozens of others.

“(Police) said ‘we heard gunfire’,” Nicholson said. “Nobody had a gun. Nobody fired anything. I remember running and crawling on the ground.”

Nicholson said he remembers thinking about the number of black men fighting in Vietnam.

“I though, wow, you don’t have to go to Vietnam to dodge bullets,” he said. “You can dodge them right here at home. There were blacks being sent to Vietnam to fight in a war for our country and we’re not even considered full citizens.”

All of that pain and suffering, he said, “over a bowling alley.”

Nicholson contrasted the public response over the Orangeburg Massacre with the killing of students at Kent State University in 1970.

“Everybody knew about (Kent State),” he said. “Orangeburg Massacre? Very little. You reckon it might have been because those were just black students down there at that little black school? ‘These are white students; we’ve got to let the world know.’ Wonder why the difference? I can’t say. No one can say.”

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis. In June, presidential candidate and brother of JFK, Robert Kennedy, also was killed. In October, at the Mexico Olympics, John Carlos and Tommie Smith stood on the medal stand after placing first and second in the 220-yard dash and defiantly raised their fists in a “black power” salute.

Nicholson admits he held on for a long time to the anger he felt over the Orangeburg Massacre, even after he began teaching and coaching.

“I came to the realization – I don’t care how upset you are about the massacre, it’s not going to change anything that happened,” he said. “What you need to do is get involved in the community to try and make a difference.”

And so, he did, running first and getting elected to Greenwood City Council in 1982.

“I had a lot of encouragement,” Nicholson said. “A lot of people said ‘you can’t do it’ and that was my encouragement.”

Nicholson served 11 years on council and later ran a successful campaign to become Greenwood’s first black mayor. In 2008, despite living in a district that is mostly Republican and mostly black, the Democrat defied the odds and served three terms as a senator in the S.C. General Assembly.

Nicholson said a lot has changed in the U.S. but there still work to be done. When he became mayor, he said, a reporter asked him how it felt to be the city’s first black mayor. But Nicholson said he wanted to be remembered as the first mayor who “happened to be black” and asked that he be measured against all mayors – not just black mayors.

“That’s what the fight has always been about,” he said. “Equality. Opportunity. Having an opportunity to pursue the same things in life that everybody else would like to have.”

Nicholson said he hopes people will focus more on the words to the Pledge of Allegiance than whether or not people stand for the National Anthem. The Pledge, he reminded, ends with the phrase “liberty and justice for all.”

“We’re not at that point yet,” he said. “We’re not at the point where we have liberty and justice for all. It’s liberty and justice for some but hopefully we will get to the point where there is liberty and justice for all.”