A Sampling of Presbyterian Attitudes Toward Slavery in the 1850s

June 2013

This month Sarah Leckie, the long-time Archives and Special Collections Assistant is posting our Blue Notes column. Sarah is working on her Masters of Library and Information Science at the University of South Carolina and has done some research for one of her classes on the college’s Historical Pamphlet collection housed here in the Archives.

The Rights and Duties of Masters, a sermon by Rev. James Henley Thornwell in Charleston, South Carolina, c. 1850

Since Thomas Paine anonymously published Common Sense in 1776, pamphlets have provided Americans from all walks of life with a means to share their thoughts and opinions on all sorts of issues, such as slavery, suffrage, education, and religion. In the 19th century, as printing costs went down and the US population grew, the use of pamphlets as a means of communicating ideas skyrocketed. Often these pamphlets began as sermons or speeches which, at the urging of supporters, the authors subsequently published. In fact, historical pamphlets could be compared to the blogs of today, in that many of them were published by and represented the views of individuals.

Presbyterian College Archives contains a large collection of historical pamphlets, many of which were originally collected by the college’s founder William Plumer Jacobs. Of the 600 pamphlets in the collection, more than 60 address the issue of slavery, and of those, 20 were published during the 1850s, a decade when key events leading up to the Civil War took place, including the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision and the Lincoln-Douglas debates. The majority of those 20 pamphlets were written by members of the clergy. This column will examine the seven that were written by Presbyterian ministers.

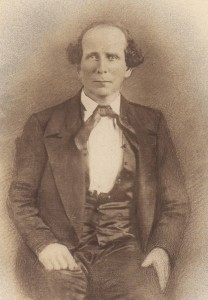

Excerpt from “Committing our Cause to God” by Rev. Ferdinand Jacobs, Sr.

In Our Danger and Duty (1850), Charleston pastor Abner Porter asserted that the Northern states were intent on ruining the South and compared the Southern states to the Old Testament’s twelve tribes of Israel. He identified South Carolina as Judah, “alone, solitary, the one faithful to herself and to all” in defending slavery (p. 9). Meanwhile, Northern pastors Ichabod Spencer (Fugitive Slave Law: the Religious Duty of Obedience to Law, 1850) and Henry Boardman (The American Union, 1851) were hesitant to condemn slavery. In fact, both men supported compromise with the South, citing the Fugitive Slave Law as the sort of appeasement that was necessary to avoid civil war, which both saw as a greater evil than slavery. Another Northern proponent of compromise was Nathan Lord, president of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire from 1828 to 1863. The collection includes two pamphlets written by Lord; in one, he referred to slavery as “a wholesome and necessary ordinance of God” (Letter of Inquiry to Ministers of the Gospel of All Denominations, on Slavery, 1854, p. 27), and in the other he called slaves “undisciplined and barbarous hordes” (A Northern Presbyter’s Second Letter to Ministers of the Gospel of All Denominations on Slavery, 1855, p. 21) who benefited from the civilizing influence of their masters.

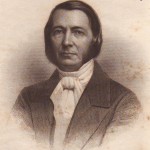

James Henley Thornwell, D.D.

Other authors represented in this collection had close ties to Presbyterian College. In The Rights and Duties of Masters (1850), a sermon by James Henley Thornwell, the author argued that slavery did not strip a man of his rights any more than any other social arrangement in which participants were not absolutely equal. It is uncomfortable to realize that the man making this argument was so admired by William Plumer Jacobs that he named Thornwell Orphanage (which Jacobs founded) in his honor.

Rev. Ferdinand Jacobs, Sr.

Even more discomfiting, Ferdinand Jacobs, the father of William Plumer Jacobs, presented his justification of slavery in The Committing of Our Cause to God (1850), contending that the Declaration of Independence’s statement that all men are created free and equal was “manifestly erroneous” (p. 7).

From the perspective granted by over a century and a half, it is easy for modern readers to condemn both those statements and the men who made them. Unquestionably, the statements themselves deserve condemnation and repudiation. However, the men who made them must be viewed as multi-faceted human beings who were products of their time and place. They were in the middle of a tumultuous time in the history of our nation, and every option for resolving the issues at hand seemed fraught with peril. In fact, in some aspects that time is startlingly similar to the present time. The pamphlets discussed here offer a fascinating glimpse into the national conversation that was taking place during the 1850s as the people of the United States wrestled not only with the issue of slavery but also with concerns about whether their fellow Americans were people of good character and good will. The accusations that flew back and forth seem all too familiar to us today, and they offer an interesting perspective on current national controversies and the ways in which they are addressed.