Martha Duckett Dendy

March 2012

We are going to combine our blogs for Black History Month and Women’s History Month into one this year, and profile the life of an extraordinary African-American woman who had an impact on both the town of Clinton and Presbyterian College. While she has been profiled many times in articles and exhibits both in Clinton and at PC, her whole life story has rarely been told.

Martha Duckett, the daughter of freed slaves, was born near Joanna in 1867. Her family had resettled there from Florence, Alabama, at the end of the Civil War. Judge Earl Young Dendy, called just “Young”, was the son of slaves Turpin Simpson and Caroline Rowland, who worked on the plantation of Joseph J. Rowland in Laurens County. At the end of the Civil War, Turpin Simpson decided to change his last name to that of his first owner, and became Turpin Dendy. Martha Duckett and Young Dendy were married in 1886. Young Dendy was already working as a skilled carpenter, and later designed and built homes for some prominent Clinton people, including George W. Young and J.W. Copeland. In 1888, already with two children, Martha established a laundry business which catered largely to students at the fledgling Clinton College (now Presbyterian College). In the early days, she would wash the clothes in big iron kettles over open fires in her back yard. Ironing in those days was done with flat irons, heated either over the fire or on a wood-burning stove.

Martha Dendy’s advertisement

1931 Pac Sac

The Dendys eventually had nine children, and managed to send all of them to college. The children also helped with the laundry business. David Dendy remembers picking up and delivering laundry on the college campus right up until he went to college himself. “I remember the charge in those early days was 25 cents a bundle – and you could put everything in the bundle. At one point, she had four local women working under her. By the time my mother retired from this work, her prices were by the piece at commercial rates, and the students brought their washing to her house.” That house, built by Young Dendy on North Adair Street, is still standing.

Martha Dendy formed close bonds with many of the students she worked for. As David Dendy remembered, “Mama thought a great deal of the many PC students she came to know through the years, and they returned her respect and affection. Once she made a loan to a student who needed just a little more money to finish his senior year. He graduated and repaid her soon after.”

While Martha Dendy herself had little formal education, she had what David called “a native intelligence and driving ambition,” things that she passed along to her children. David remembers that whenever his mother hung the college diploma of one of his older siblings on the wall, it made him more determined to earn one of his own.

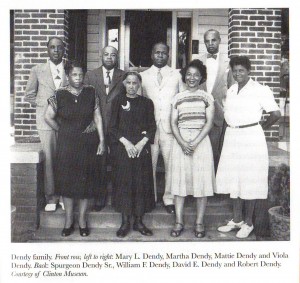

The children did pursue their educations, and some of them moved out of the area after they graduated. Robert Dendy, a graduate of South Carolina State University, went to New York City, where he worked for the postal service. William Dendy, a graduate of South Carolina State and Meharry Medical College, became a dentist in Evansville, Indiana. David Dendy graduated from Morris Brown University, and did post-graduate work at Howard University and South Carolina State. He was principal of the St. Alban Training School in Simpsonville for twenty-five years before returning to Clinton as principal of what was to become the Martha Dendy School. He was also very active in the Clinton community, working with the Housing Authority, the Planning Commission, the Chamber of Commerce, and the YMCA.

The Dendy Family

Not all of Martha and Young Dendy’s children, however, were to have such successful futures. Unfortunately the life of one of her younger sons, Norris Dendy, was cut short at the hands of a mob in Clinton on July 4, 1933. Norris, then a 35-year old married truck driver who was living and raising his five children in Clinton, got involved in an altercation with Marvin Lollis, a white truck driver, during a Fourth of July outing. Insults were exchanged, and Dendy hit Lollis. As he returned to Clinton, Dendy was arrested by local police in nearby Joanna, and sent to the Clinton jail. Later in the evening, while the police chief was at home and the deputy was out on patrol, a mob forcibly removed Norris Dendy from his cell and carried him away in a car. His mother, wife, and children stood helplessly by while the caravan of cars drove out of town. This was the last time he was seen alive. His body was recovered the following morning in the Sardis churchyard near Renno. He was bruised and had suffered a fractured skull. Ropes were found near the body. The story appeared in the national media, and pressure from Norris’ brother Robert kept the case in the spotlight. Eventually five local men were brought before two different grand juries, but key witnesses were reluctant to appear, and no one was ever indicted in the case.

Young Dendy, Sr. died in 1940. Martha Dendy retired from her laundry business in 1950, and died in 1953 at the age of 86. By the time of her death, she had become quite prosperous, and owned considerable residential and commercial property in Clinton. In 1974 three of the Dendys’ children, David E. Dendy and Robert Y. Dendy of Clinton and Dr. and Mrs. William F. Dendy of Evansville, Indiana, donated funds to establish the Martha and Young Dendy, Sr. Scholarship at PC. This was the first scholarship ever established by an African-American at the college, and came just five years after PC admitted its first black student. According to David Dendy, “My brothers and I thought the scholarship at PC in memory of our mother would be appropriate because here was her life’s work and where she made the money for the opportunities…we believe this scholarship says something. It will help black students and white students to get a good education at Presbyterian College. I know Martha Dendy would like that very much, because she believed so strongly in education.” In an editorial he wrote at the time for the Clinton Chronicle, editor Donny Wilder called the gift “one of the strongest testimonials I have ever seen to the fruits of hard work, thrift, business acumen and an appreciation for education.”

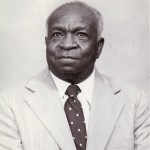

David Dendy 1976

David Dendy himself maintained a strong relationship with Presbyterian College. He served on the Board of Visitors and was awarded an honorary degree in 1976. He was the first African-American in the college’s history to be given such an honor. He was also honored by the town of Clinton, receiving its Citizen of the Year Award in 1975 for his involvement in various community organizations and his work as an ambassador of goodwill between the white and black communities. In that same editorial, Donny Wilder summed it up this way: “Distinctions between black and white have never bothered David Dendy. We’re all just people to him. He and his family have worked hard and have earned their financial rewards. They have been generous in their contributions to this community, and that includes the entire community. I can’t help but believe that this must have been what Martha Dendy had in mind as she spent those long hard hours over the wash pots years ago.” David Dendy died in 1985 at the age of 83.

Martha Dendy’s name is still visible around Clinton today. There is of course the Martha Dendy School, which has recently served as a sixth grade center. Nearby is Martha Dendy Drive. And near downtown is the Martha Dendy Service Center, which is now abandoned. Through David Dendy, her influence lived on both in the town and at the college. And it continues to live on at Presbyterian College through the scholarship that her children established in her honor, where, since 1974, it has helped twenty students to attend PC.

(Quotes from David Dendy are taken from an article in the Presbyterian College Report, May 1974.)