“Stonewall” Jackson and his Presbyterian Journey

February 2013

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson is a major focus of a collection donated to the Presbyterian College Archives in 1999 by Ernest J. Arnold, PC class of 1936. The Jackson-Arnold Collection was compiled by Thomas Jackson Arnold of West Virginia, the nephew and namesake of Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson.

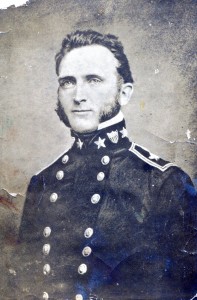

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, retouched copy of 1853 image by Matthew Brady

The name “Stonewall” Jackson evokes images of smoky Civil War battlefields where generals struggled to out-maneuver their opponents. Jackson received his nickname while a Confederate general at the Battle of First Manassas (also known as the First Battle of Bull Run). General Bernard Bee of South Carolina described Jackson and his troops as “standing like a stone wall.” Bee, a talented general himself, was mortally wounded later that day and is buried in Pendleton, South Carolina.

Jackson was well known for his tactical military skill, which may be attributed to his training at West Point and an early interest in the battles of Napoleon, Francis Marion (the Swamp Fox of Revolutionary war fame), and Old Testament military leaders. After graduating from West Point in 1846, Jackson made a name for himself during the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. Jackson and his classmates, in the right place at the right time, were called into service.

After the Mexican War, D. H. Hill, a friend and a professor of mathematics at Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, helped Jackson secure a professorship at Virginia Military Institute where he taught Physics until the Civil War began. Once again, the professor and the VMI cadets were in the right place at the right time. Jackson believed in preserving the Union, but when Virginia finally seceded, he joined the Confederacy because he believed in “states’ rights,” that the states were sovereign, controlling their own legislatures, magistrates, militias, and money, and that his native state ranked above his country.

In addition to being a skilled military tactician, Jackson also became a staunch Presbyterian. From the age of seven, Jackson along with his younger sister, Laura, was raised by his late father’s family at Jackson’s Mill, south of his birthplace, Clarksburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), on the West Fork River of the Monongahela. The Jackson clan was a rough bunch living a hardscrabble life on the river and surrounding land. As a boy, Jackson was expected to work at the mill, which included felling trees, plowing, caring for livestock, and making syrup. Religion was non-existent at Jackson’s Mill. His mother, Julia Neale Jackson, had been a devout Presbyterian raised in a prosperous family from Loudoun County in the northern Virginia tidewater area east of the Allegheny Mountains. She died of tuberculosis shortly after Jackson and Laura moved to the mill. There was some doubt about whether Jackson had ever been baptized.

While serving in Mexico, Jackson had visited with Catholic priests, discussing church doctrine and searching for principles that matched his beliefs. He came to realize that his faith did not align with Catholicism. In Lexington, he was baptized in the Episcopal Church with the understanding that he would not be bound to a specific denomination. Within weeks he was meeting and discussing doctrine with the pastor of Lexington Presbyterian Church, Rev. William Spottswood White. Through his conversations with White and John Blair Lyle, a bookseller in Lexington, Jackson came to see that Presbyterianism best matched his beliefs.

In 1851, he joined Lexington Presbyterian Church, the largest and most prestigious church in the area, and he started a Sunday school for slaves there in 1855. It is a matter of contention whether the slaves were taught to read at his “school.” According to biographer, Lenoir Chambers, at one point Jackson had up to 100 slaves attending the sessions which included “singing hymns, a short talk on a bible story, and instruction in the Shorter Catechism or some other suitable formula of truth,” led by additional volunteers. The sessions lasted “exactly forty-five minutes, never more, never a minute more.” The Sunday school continued into the 1880s, “brought to a close only when necessity for its continuance had passed away.”

Jackson collected alms for his church, and was systematic in tithing, often giving more than a tenth of his income to the church. He was elected Deacon in 1857 at the time when deacons were first elected.

Through books borrowed from Lyle and the resulting discussions concerning the power of prayer, prayer became a “habitual practice” for Stonewall Jackson. Many sources say that he prayed every time he took a drink of water or a bite of food, when he mailed a letter or opened a letter, appealing for good news or strength to bear bad news. According to his wife, Anna Morrison Jackson, when asked if he ever forgot to pray, he said, “I can hardly say that I do; the habit has become almost as fixed as to breathe.”

To further illustrate the extent to which Jackson had found his place in the Presbyterian Church, he married twice in his last ten years, each time to the daughter of a Presbyterian minister. In 1853 he married Elinor Junkin, the daughter of George Junkin, the president of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University). Sadly, Elinor and their child died in childbirth the next year. In 1857 he married an earlier acquaintance, the sister-in-law of his friend D. H. Hill, Mary Anna Morrison who was the daughter of Robert Hall Morrison, the president of Davidson College.

Stonewall Jackson’s military accomplishments are well known. By examining his life as a man of faith, we hope to provide a more complete picture of him as a whole person.