Something Rubbed Off: Black History Month

February 2010

Since February is Black History Month, we thought it would be interesting to include a reminiscence from a PC grad on race relations during his time at the college.

Charles Joyner ’56

Charles W. Joyner graduated from PC in 1956, thirteen years before the first African-American student was admitted to the college. After graduation, he received a Ph.D. in history from the University of South Carolina, and an additional Ph.D. in folklore and folklife from the University of Pennsylvania. He has taught at St. Andrews College, the University of Alabama, and Coastal Carolina University. He is an authority on Southern history and is the author of several books, including Down by the Riverside, and Folk Song in South Carolina.

He received an honorary degree from PC in 1993, and the college’s highest alumni award, the Gold P, in 2000. He is also a recipient of the Governor’s Lifetime Achievement Award, given annually by the governor of South Carolina and the South Carolina Humanities Council. His story was originally published in John Boles’ Shapers of Southern History: Autobiographical Essays (Athens, University of Georgia Press, 2004).

“Ultimately I went away to college. Nobody in my family had ever graduated from college before. In fact, neither of my parents had finished high school. To this day, I do not understand why they were so fiercely determined that their children would have college educations. But the abundance of summer jobs for their children in Myrtle Beach helped to make their dream financially possible. I went away to Presbyterian College, in the upstate college town of Clinton, South Carolina, where I majored in history and English. The new freshman class brought the student enrollment to just over 500. We were a homogeneous lot on the whole, overwhelmingly male and almost all southern white Protestants. Sprinkled among us were fewer than a dozen women, a few Catholics, and a handful of Northerners. When I arrived at Presbyterian College, World War II had been over less than a decade, and there were still a good many veterans in the student body. They lent an aura of seriousness to our classrooms.

Charles Joyner in 1956 Pac Sac

These were years of striving for self-discovery, trying to attain a clearer personal understanding of life’s essentials. Most of us experienced personal crises of love, faith, friendship, and death among friends or family while at Presbyterian College. But little in the classrooms challenged our provincialism, or our complacency, or our racism in those placid years of the 1950s.

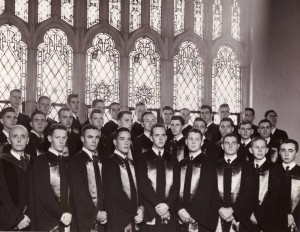

The real challenge to my provincialism came from an unexpected quarter–the college choir. Dr. Edouard Patte, our Swiss-born choir director, announced early in the spring of 1954 that on our spring tour through the Deep South we were going to sing at Stillman College, a black Presbyterian institution in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. We would be guests of Stillman, he said; and as they would be gracious hosts, we must be gracious guests. He expected us to be friendly, shake hands, and live up to the South’s reputation for good manners. Without preaching (although he was an ordained minister), Dr. Patte did more to instill in his choirboys a Christian understanding of the relationship of all God’s children to one another than either our chapel services or our formal education. But southern etiquette at the time did not countenance interracial handshaking. Dr. Patte left it up to us, but he did not make it easy to dodge the dilemma. If we were unable, or unwilling, to be gracious guests, we were not required to come along on the trip. But of course, we knew that if we did not make the trip, we would miss our visit to New Orleans.

PC Choir, 1954

The choir members reacted in varying ways. I remember one student who dropped out of the choir then and there, although he never acknowledged his reason. Another announced that it did not bother him one bit. He had got on well with “darkies” all his life, he said. That student would later move beyond such condescending paternalism to become one of the most eminent ministers in our denomination and a personal friend of several important civil rights leaders. Despite my heterodox notions about the Civil War, I was no rebel against segregation then. Segregation, after all, still prevailed all over the country. In my quiet and timid bigotry I said nothing, but inwardly I determined that I would not enjoy it and that I certainly was not going to shake hands with any black students.

Against my better judgment, I relished our visit to Stillman College immensely. We ate with our hosts in the college dining hall and attended their choir rehearsal. Their singing put us to shame. At our own concert that night, the “Amen” we sang following Dr. Patte’s benediction was so dreadfully out‑of‑tune that even Stravinsky would have found it discordant. The “Stillman Amen” became legendary in the choir. Despite our embarrassment, we all enjoyed our visit to Stillman. For me it was life-changing. Despite my earlier resolution, I did shake hands with black students. The color did not rub off, but I know something had.