S.C. attorney addresses originalist interpretation of U.S. Constitution during lecture at PC

One of South Carolina’s leading civil and employee rights advocates made a compelling case against a conservative interpretation of the U.S. Constitution during a lecture Tuesday at Presbyterian College.

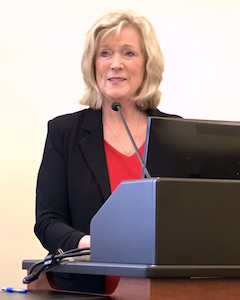

Malissa Burnette

Columbia attorney Malissa Burnette spoke to a large group of students, faculty, and community members during PC’s annual Constitution Day event, where she argued against the conservative legal principle of “originalism.”

Originalists, she said, believe that the meaning of the Constitution is fixed and bound by the original intent of the country’s founding fathers. Burnette said she first heard this legal theory pronounced by S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson during the state’s case against same sex marriage. As a defendant in the case, Wilson proclaimed that the founding fathers never contemplated marriage as anything other than between a man and woman and, thus, could not be otherwise.

“In other words, they argue that the Constitution is a static document – that the words in the Constitution should mean exactly what they meant when the founders wrote it and it never evolves,” she said.

But Burnette argued that the founders also lived during the period when slavery was legal and women did not have the right to vote. She then asked Wilson and other originalists if they endorsed slavery and stripping women of their right to vote.

While same sex marriage was seemingly settled by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2014, Burnette said the current court has new standard bearers for originalism — new justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh – who agree with Justice Clarence Thomas.

Burnette said Justice Coney Barrett, though, understands that originalism can be a “destructive force.” In her writings, Coney Barrett suggests that the court should decline hearing cases where originalism would be detrimental, such as Brown vs. Board of Education, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine in segregated public schools.

The Supreme Court did vote to strike down Roe vs. Wade, however, by using originalist arguments against a 50-year legal – and popular – precedent. If the court does so again, Burnette said, it could be the end of the line for same-sex marriage, and other legal protections protected by precedent but not explicitly codified.

Oddly, she pointed out, abortion was not originally forbidden in the U.S.

“Abortion has been in place for centuries,” Burnette said. “It’s necessary. We say now that abortion is healthcare. It’s been healthcare for a long time. It was legal when the Constitution was written up until the time that the fetus could be felt moving in the womb.”

When conservative Justice Samuel Alito argued that abortion is not deeply rooted in the country’s history and tradition, Burnette said he ignores that some things – desegregation, freedom from slavery, women’s right to vote – were not always a part of U.S. history.

“We’re going to start seeing decisions that are going to challenge these rights that we’ve taken for granted,” she said. “And we’ll have to fight these fights all over again.”

Burnette said the Constitution clearly is a living document.

“We need to admit that the Constitution is not perfect and that it needs to evolve with the times,” she said. “I think we already know because it has been amended 27 times. So, it wasn’t perfect to begin with.”

Even the Founding Fathers argued early on how the Constitution should be interpreted. If James Madison, for example, had won his arguments, there would be no federal highway system and no national treasury because the Constitution does not spell out the federal government’s responsibility for banking or roads.

“These disputes among the founders illustrate the impossibility of determining today the intent of authors who wrote words over 200 years ago,” Burnette said “The founders didn’t even agree among themselves. The fact that their intent cannot be accurately determined, makes decisions based on originalism’s premise especially vulnerable to political exploitation in my view.”

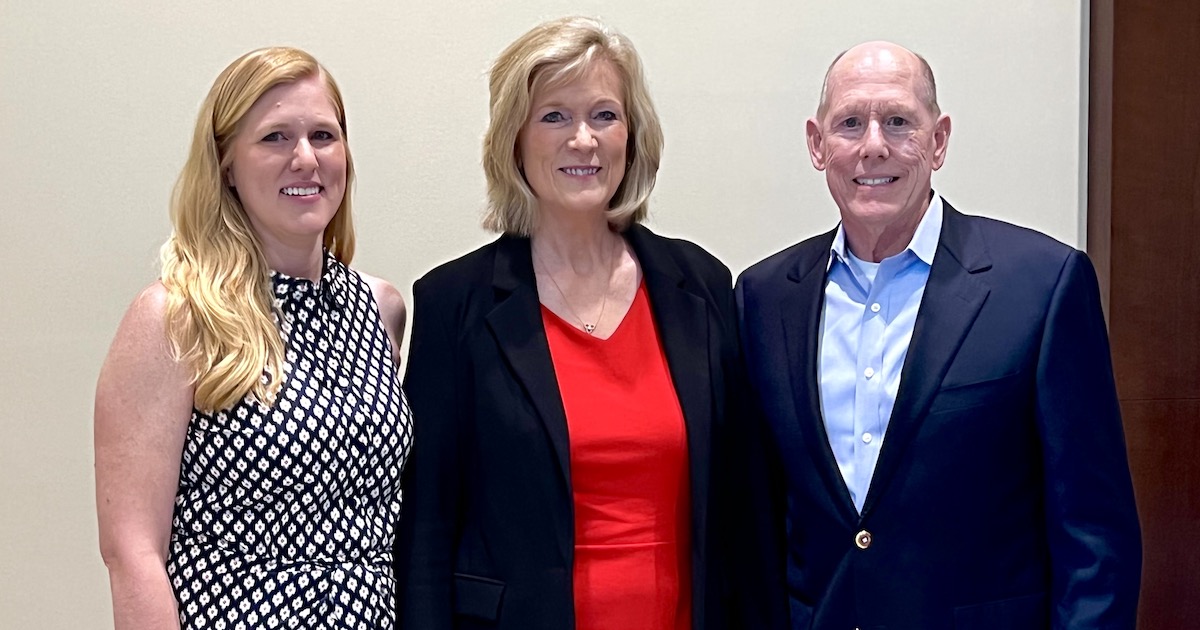

Burnette’s husband, Mike LeFever is a 1969 PC alumnus. Their daughter, Grant LaFever, is a 2013 alumna and also practices law.

(Left to right) PC alumna Grant LeFever ’13, guest speaker Malissa Burnette, and PC alumnus Mike LeFever ’69.