Presbyterian College president Dr. Anita Gustafson gives ‘boisterous and bold’ lesson on history of women in higher education

Presbyterian College’s first female president, Dr. Anita Gustafson, with the college’s first female SGA president, Ginny Nichols Cartee ’74.

Presbyterian College’s first female president shared women’s struggles to find their place in higher education during an inspirational speech Wednesday in honor of Women’s History Month.

In her lecture, “Boisterous and Bold: Women in Higher Education,” Dr. Anita Gustafson, the 20th president of PC, began by noting her own place in the college’s 144-year history.

“I’m really honored and excited to be the first woman president of Presbyterian College,” she said. “In all honesty, though, I don’t think about it on a daily basis. I just try to do my job. I just do the work that’s before me. But I do think it’s important to reflect on the historical journey women have had in higher education because it’s not that long ago that it would have been unthinkable for a woman to have had this opportunity. So, I do want to be very grateful for the pathway of the women who have come before me – who have paved the way for me.”

Gustafson began with the inspiration for her speech’s title, which emerged from the early 20th-century debate in Virginia on allowing women to be admitted to the University of Virginia. Opponents, she said, claimed – in the negative – that educated women would be “boisterous and bold.”

“I think the real issue with women getting into higher education – getting a college education – was the basic problem of an educated woman, which was educated for what?” she said. “What was the ultimate purpose of her education?”

Gustafson said that in the republic’s early days, educational opportunities were limited to white women from property-owning families whose husbands and sons were eligible to vote. Another argument in favor of educating women was that they should learn domestic arts and how to create a strong home environment.

“This was the argument for educating middle-class white women in the early 19th century,” she said. “Any educational opportunity that might break women out of that domestic sphere was seen by critics as dangerous to the very fabric of society.”

Mary McLeod Bethune (Bethune-Cookman University)

But, oddly enough, Gustafson said there were new opportunities for African-American women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 1880s, white northerners founded Spelman College in Atlanta, which offered a liberal arts education to black women. In 1904, South Carolina native Mary McLeod Bethune started a girls’ school in Dayton Beach, Fla., that evolved into a women’s college and merged with a men’s institution in 1943 as Bethune-Cookman College.

Showing a picture of her mother as a young nurse-in-training, Gustafson said nursing and teaching were two of the few professional opportunities available to most women in the early 20th century.

“They were available for women because they were seen as lying within her domestic sphere, so they were non-threatening to her traditional role,” she said. “Teaching and nursing were very important professional opportunities for women for many, many years in history. And that certainly was the case for my mother. My mother was very proud of being a nurse, even though she didn’t have a whole lot of other options available for her.”

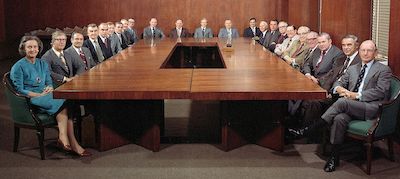

For some, the compelling purpose of an education for women was meeting a good man, Gustafson said. But for many others, it was to pursue meaningful work in a broad range of careers equal to men. Katherine Graham became the publisher of the Washington Post in the 1970s, but as Gustafson showed in a picture of the newspaper’s board of directors, she was the lone female voice.

Katherine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post, is the lone female in the boardroom. (AP Shutterstock)

“This gives you an idea of how rare it was for a woman to have a seat in the boardroom,” Gustafson said. “She was the first woman to be on the board of the Associated Press and the first woman to lead a Fortune 500 company. And she had a seat at the table, but there was only one of her, right? So, she was definitely boisterous and bold.”

The plight of working-class women – both white and black – was even more restrictive, and some had no chance of attending school at all, much less college, Gustafson noted. However, throughout history, women have marched toward equality.

Gustafson cited one example: 18th-century Englishwoman Mary Wollstonecraft, the mother of Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, who published her book, The Vindication of the Rights of Women, in 1792. Wollstonecraft’s book was a written response to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile, which expressed his belief that women were naturally inferior to men.

“Women’s nature, he said, is different from men,” Gustafson said. “Therefore, they require a different education, an inferior education from men. This is what he wrote. He said, ‘Little girls always dislike learning to read and write. But they are always ready to learn how to sew.’ Well, no surprise, Wollstonecraft disagreed. She said human nature is common to both sexes. That women are inferior is the fault of the system, not caused by nature. You could call it systemic sexism, actually. She wrote that society stunts women, and education has the potential of remedying the situation if they can have access to it. Wollstonecraft set the intellectual framework for women’s educational equality and intellectual capacity, but it took a couple of centuries for that to bear fruit.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the daughter of a Massachusetts judge, was another champion for women’s rights to education and equality, according to Gustafson. Though she read from her father’s library and kept up with the same lessons as her brothers, Stanton’s father lamented that she had limited options. Stanton attended one of the few institutions available to women, Troy Female Seminary, but found it deficient because it was only a place for women to learn to be good Christian homemakers or teachers.

In 1848, Stanton joined abolitionist Lucretia Mott and African-American leader Frederick Douglass to hold the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, N.Y., where they produced the Declaration of Sentiments.

“Using the Declaration of Independence as a model, they declared, all men and women are created equal,” Gustafson said. “That men have created a system of tyranny over women. That women have been denied the vote, their rights as citizens, the right to own property, and man has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education, all colleges being closed against her.”

Eventually, liberal arts institutions and women’s colleges were founded, and women secured the right to attend the same schools as men, especially during periods like the Civil War and World War II, when colleges could keep their doors open by admitting women. However, once the wars were over, women were expected to step aside again and settle for professional careers like teaching, nursing, or serving in offices as secretaries.

In 1963, Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, which gave voice to the rising frustrations of women who felt trapped in the suburbs with little to do, Gustafson said.

“She called this a problem that has no name,” Gustafson said. “She helped channel this unhappiness into the birth of second-wave feminism of the 1960s. For the record, the problems noted by Friedan were in many ways a luxury when compared to the discrimination felt by black women. Black women were excluded from the suburbs, and in many families, they had to work at low-paying jobs since their husband’s earning potential was also limited. And those women gave birth to the youth of the Civil Rights Movement, many of whom became involved as elderly stateswomen. Women such as Rosa Parks, whose actions kicked off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Ella Baker, who was a grassroots activist, worked closely with the young leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And Fannie Lou Hamer, who was a fiery spokesperson for the Freedom Democratic Party in 1964.”

Florence Jacobs, the daughter of Presbyterian College founder William Plumer Jacobs and one of the college’s first graduates.

Gustafson said this was the era when women were first introduced as residential students at PC. Women have been part of PC since its founding in 1880, and, in fact, its first three graduates were women — Rebecca Boozer, Jessie Lee Copeland, and Florence Lee Jacobs, the daughter of founder William Plumer Jacobs. Another woman, Anna Austin, was valedictorian of the class of 1910 and became South Carolina’s first female medical doctor of obstetrics and gynecology.

But none of them lived on campus.

“By 1915, there were only 11 students,” Gustafson said. “PC’s motto at the time was, ‘Where Men Are Made.’ Between 1921 and 1931, no women were admitted because the Presbyterian Synod of South Carolina founded a women’s college in Columbia. It was called Chicora College, and they wanted to direct all the Presbyterian women there.”

When Chicora merged with Queens College in 1930, PC again admitted women, and it was soon apparent that attitudes amongst the new students had changed, Gustafson said. Alice Benjamin wrote “On Being a Coed” in a 1932 edition of the PC Magazine, where she stated:

“At the beginning of the year, we took seriously the masculine idea that boys know more than girls. We listened attentively when they opened to us their spacious minds. But it didn’t take us long to realize that masculine knowledge is mostly masculine bluff. Now we listen jubilantly and allow them to get what satisfaction they can from telling us things that we already know.”

In 1963, the college announced it was going fully co-educational to “gradually nurture future female leaders of the Presbyterian Church.”

“But from my perspective as a college president, I am sure that the realization that by admitting women, PC would also significantly grow their enrollment and thereby add to the resources of the college, I’m sure that was high on the list as well,” Gustafson said. “The leaders of Presbyterian College may not have read Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique, but it was published that same year, 1963, and times were indeed changing. The civil rights movement was underway, and the women’s movement would soon burst on the scene. In the fall of 1965, PC admitted 35 residential students, making the class of ’69 the first one to include significant numbers of women.”

Presbyterian College’s first coeds during the late 1960s.

The percentage of women attending PC continued to grow, and by 1974, women made up about 35 percent of the student body. Still, rules for women during that period were more restrictive than for men, Gustafson said. Women were subject to curfews and had to be accompanied if they left campus after 7 p.m. They were also required to wear dresses for classes other than physical education.

“Women came to PC for many different reasons,” and here, the women on the left are having a great time, and they’re not wearing dresses, by the way. They appreciated the small school and small-town atmosphere. Many had brothers, fathers, or pastors who attended the school. But without a doubt, their PC education transformed their educational pathway.”

Women’s arrival changed PC, as well. The college emphasized fine arts, particularly music, modern foreign languages, and philosophy. Marion Hill was hired as the first women’s dean of students. Eugenia Carter, the first woman to teach at PC, was joined by three new female faculty members – Ann Moorefield in English, Dr. Anne Stidham in psychology, and Lucretia Hunter in mathematics. As the school grew, so did the number of women serving on the faculty, adding Dr. Dottie Brandt in education, Jane Holt in biology, and Dr. Yvonne King in French. Women also joined the board of trustees in 1968 – Dr. Virginia Hardy from Clemson and Dottie Fuqua from Atlanta.

Those early days on campus were not always easy for women, however. Gustafson said women were initially denied leadership positions and were not allowed to attend ROTC. In 1970, an article in The BlueStocking entitled “Coeds Express Frustration” expressed women’s frustration with the dress code, among other things. More than 150 women signed a petition and wrote a letter to the paper that said:

“As women students at PC, we are concerned with the denial of our right to establish our own value system. The outdated dress code puts emphasis on creating the illusion of femininity while ignoring the more important concept of feminine behavior. We see no point in paying $2,375 a year to be told how to dress. Not only because it denies our individuality but also because it contradicts the fact that outward appearances should be secondary to inward character. We look forward to the day when PC will no longer stand for Presbyterian Convent, and the school will get down to the business of educating us rather than legislating morals.”

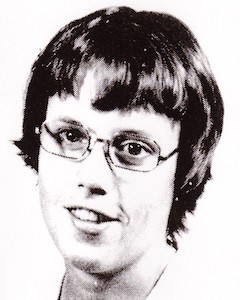

Ginny Nichols Cartee ’74, PC’s first female SGA president

Women were also ready to become leaders on campus, Gustafson said. In 1973, Ginny Cartee became the first woman to be elected president of the Student Government Association.

“Overall, women who attended PC in the 60s and 70s valued their experience here,” Gustafson said. “They believed that PC was and still is a great college, and the friends that they made here are like a second family to them.”

Women eventually made their way into executive offices at PC, including cabinet members like Margaret Williamson, vice president of enrollment from 1982 to 1987, Genevra Kelly, vice president of advancement, and Val Shealy, PC’s first female athletic director.

Gustafson was the first female to lead the college’s academic office as interim provost from 2010 to 2012.

“I have had the honor to meet so many of the women who attended PC in those early years, and they’re really thrilled that PC has a female president now,” she said. “So, I’m very honored to be that president.”

It was not a foregone conclusion that she would enter higher education, however. Gustafson said careers were opening up for women in her generation, but old attitudes remained, even inside her own family.

“I loved my dad,” she said. “He was very kind and loving to me, but he was definitely old school, And these were his messages to me, because he would kind of tell me these stories over and over and over again when I saw him. He’d say, don’t show people how smart you are because no man wants to marry a woman who is smarter than he is, or who at least appears to be.”

Gustafson’s father did not live long enough to see his daughter begin her career as an academic, much less a college president. Still, her mother and stepfather were always supportive, as was a mentor at North Park University who said her life and career were a journey and not to fear taking the first step.

Gustafson also gave some advice to the students in the room as they contemplate their own futures – both men and women.

“Always show up,” she said. “Do your best in whatever you are doing. Be a builder. Don’t be afraid of the next step, of taking some risks. Don’t sell yourself short. And remember that you belong in the room. You belong at the table.”